Important Note

The Billy Jurges / Violet Popovich part of this web page is out of date, as I have expanded my research into book form. See below:

Book out on the shooting of Billy Jurges!! My latest book, published by The History Press of Charleston, South Carolina (an imprint of Arcadia Publishing) is The Chicago Cub Shot for Love: A Showgirl’s Crime of Passion and the 1932 World Series.

Here is a summary of the book, taken from the back cover: “In the summer of 1932, with the Cubs in the thick of the pennant race, Billy Jurges broke off his relationship with Violet Popovich to focus on baseball. The famously beautiful showgirl took it poorly, marching into his hotel room with a revolver in her purse. Both were wounded in the ensuring struggle, but Jurges refused to press charges. Even without their star shortstop, Chicago made it to the World Series, only to be on the wrong end of Babe Ruth’s legendary Called Shot. Using hundreds of original sources, Jack Bales profiles the lives of the ill-fated couple and traces the ripple effects of the shooting on the Cubs’ tumultuous season.”

Here is a summary of the book, taken from the back cover: “In the summer of 1932, with the Cubs in the thick of the pennant race, Billy Jurges broke off his relationship with Violet Popovich to focus on baseball. The famously beautiful showgirl took it poorly, marching into his hotel room with a revolver in her purse. Both were wounded in the ensuring struggle, but Jurges refused to press charges. Even without their star shortstop, Chicago made it to the World Series, only to be on the wrong end of Babe Ruth’s legendary Called Shot. Using hundreds of original sources, Jack Bales profiles the lives of the ill-fated couple and traces the ripple effects of the shooting on the Cubs’ tumultuous season.”

I’ve therefore removed much of the essay on Billy Jurges and Violet Popovich that used to be on this webpage, though I’m leaving some of the text, photographs, and captions to provide an idea of what occurred on July 6, 1932. Drew Gallagher reviewed my book for the Fredericksburg, Virginia Free Lance-Star on July 25, 2021, and he also interviewed me in my kitchen, in front of numerous Cubs photographs, a few days before that (you may have to scroll down to get below the pop-up ad after clicking on the link).

. . . . .

The New York Times related that she “made one final plea for his love” and pulled a small revolver from her purse. As Jurges made “a wild lunge” for it, the gun went off. One bullet “struck him in the right side, ricocheted off a rib and came out the right shoulder. The second ripped the flesh about the little finger of his left hand.” The third bullet hit Popovich, striking her in the left hand and traveling “up the arm six inches.”

The New York Times related that she “made one final plea for his love” and pulled a small revolver from her purse. As Jurges made “a wild lunge” for it, the gun went off. One bullet “struck him in the right side, ricocheted off a rib and came out the right shoulder. The second ripped the flesh about the little finger of his left hand.” The third bullet hit Popovich, striking her in the left hand and traveling “up the arm six inches.”

The Hotel Carlos (which for many years was known as the Sheffield House) is just a couple of blocks north of Wrigley Field at 3834 North Sheffield Avenue. (Click on image to enlarge.)

. . . . .

As one might expect, the news media pounced on this story. Just a few hours after reporters first heard the news, Chicago’s Daily Illustrated Times was on the street with a banner headline: “Bill Jurges Shot By Spurned Cabaret Girl,” followed by “Singer and Ballplayer Wounded in Love Tiff Gunplay.” A photo of Popovich and one of Jurges lying in his hospital bed (wearing “a smile as well as a couple of bandages”) were also splashed on page 1. Above the photographs was the caption “Singer and Ballplayer Wounded in Love Tiff Gunplay.” The headline of that afternoon’s Chicago Daily News was “Jurges, Star Cub Is Shot,” followed by “Girl Wounded in Hotel Mystery; Both Will Live.” (Click on image to enlarge.)

As one might expect, the news media pounced on this story. Just a few hours after reporters first heard the news, Chicago’s Daily Illustrated Times was on the street with a banner headline: “Bill Jurges Shot By Spurned Cabaret Girl,” followed by “Singer and Ballplayer Wounded in Love Tiff Gunplay.” A photo of Popovich and one of Jurges lying in his hospital bed (wearing “a smile as well as a couple of bandages”) were also splashed on page 1. Above the photographs was the caption “Singer and Ballplayer Wounded in Love Tiff Gunplay.” The headline of that afternoon’s Chicago Daily News was “Jurges, Star Cub Is Shot,” followed by “Girl Wounded in Hotel Mystery; Both Will Live.” (Click on image to enlarge.)

. . . . .

“William Jurges, star shortstop of the Chicago Cubs, was shot in the right side and left hand while wresting a gun from Miss Violet Popovich, who is said to have attempted to commit suicide in his room in a Chicago hotel. The girl was wounded in the hand. Miss Popovich is shown a few hours after the shooting, hiding from photographers.”

“William Jurges, star shortstop of the Chicago Cubs, was shot in the right side and left hand while wresting a gun from Miss Violet Popovich, who is said to have attempted to commit suicide in his room in a Chicago hotel. The girl was wounded in the hand. Miss Popovich is shown a few hours after the shooting, hiding from photographers.”

. . . . .

Violet stands with her attorneys, Herbert G. Immenhausen and James M. Burke, in Chicago’s felony court on July 15, 1932. She is wearing, as the Chicago Daily Tribune pointed out in its article, “a white crêpe dress, trimmed in red, white hat and … red shoes.” Newspapers across the country covered the story of the show girl and the shortstop in sensational fashion. They referred to Violet as the . . . . . . . “ The bandage on her left arm covers the bullet wound she received when she struggled with Billy Jurges over the gun in his room at the Hotel Carlos.

Judge John A. Sbarbaro’s courtroom on July 15, 1932. From left to right: Herbert G. Immenhausen, defense attorney; Violet Popovich; James M. Burke, another of her attorneys; and Billy Jurges (shielding his face from photographers with a handkerchief). Although Jurges . . . . . . . . . she signed a contract–to perform in Chicago’s State-Congress Theatre, where she billed herself as “The Girl Who Shot for Love.”

. . . . .

Violet Popovich was clearly no “shrinking” Violet, and she did not waste any time capitalizing on her newfound notoriety. The above advertisement appeared in a Chicago newspaper less than two weeks after xxxxxxxx xxxxxxxx xxxxxx (The ad at left appeared in another paper. Note the reference to the “Bare Cub Girls” and the “Bare Cub Frolics” (rather than “Follies,” as in above).

Violet Popovich was clearly no “shrinking” Violet, and she did not waste any time capitalizing on her newfound notoriety. The above advertisement appeared in a Chicago newspaper less than two weeks after xxxxxxxx xxxxxxxx xxxxxx (The ad at left appeared in another paper. Note the reference to the “Bare Cub Girls” and the “Bare Cub Frolics” (rather than “Follies,” as in above).

. . . . .

This was not Violet’s first experience on the stage. A Tribune article relates that at age 17 she performed in the chorus of Broadway producer Earl Carroll’s Vanities. “After her show experience,” wrote the Tribune, “she modeled in New York for illustrations for confession story magazines. The girl has gray eyes, regular features and an olive skin.”

This was not Violet’s first experience on the stage. A Tribune article relates that at age 17 she performed in the chorus of Broadway producer Earl Carroll’s Vanities. “After her show experience,” wrote the Tribune, “she modeled in New York for illustrations for confession story magazines. The girl has gray eyes, regular features and an olive skin.”

Violet’s singing and dancing act lasted only a few weeks, though she would continue to dabble in show business. A 1937 Chicago Daily Tribune article, for example, mentions her as a “torch singer” in a city nightclub.

. . . . .

Right: This rare photograph of Violet Popovich was taken at about the time she ran away from home. It is from the collection of Mark Prescott, Violet’s nephew, who graciously allowed me to publish it on my Cubs website.

Right: This rare photograph of Violet Popovich was taken at about the time she ran away from home. It is from the collection of Mark Prescott, Violet’s nephew, who graciously allowed me to publish it on my Cubs website.

Mark Prescott gave me about a dozen or so other photographs of his aunt, some of which I have displayed in a photo gallery on this website. The saga of Violet Popovich (or Violet Valli, if you like) and her shooting of ballplayer Billy Jurges have always intrigued Chicago Cubs fans, and I thank Mark for his generosity. Below are two more photographs of her.

. . . . .

The tombstone of Violet Popovich in the Forest Lawn – Hollywood Hills Cemetery.

The tombstone of Violet Popovich in the Forest Lawn – Hollywood Hills Cemetery.

More details on Violet Popovich, her family, Billy Jurges, and the shooting are in my book The Chicago Cub Shot for Love: A Showgirl’s Crime of Passion and the 1932 World Series (The History Press, an imprint of Arcadia Publishing).

. . . . .

Once again, Violet found herself in the courtroom of Judge John Sbarbaro. Barnett was arrested and charged with extortion, larceny, and other crimes. Judge Sbarbaro ordered the letters returned and set Barnett’s bond at the rather high $10,000, explaining that . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ..

Once again, Violet found herself in the courtroom of Judge John Sbarbaro. Barnett was arrested and charged with extortion, larceny, and other crimes. Judge Sbarbaro ordered the letters returned and set Barnett’s bond at the rather high $10,000, explaining that . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ..

Right: Violet Popovich back in court (with Police Sergeant David Levin, right) after her Billy Jurges love letters were stolen by Lucius Barnett, her former bail bondsman.

Billy Jurges was doing well and soon put the entire matter behind him. Interestingly enough, when Judge Sbarbaro first met Violet Popovich in July. . . . . he added “and I hope no more Cubs get shot.” Unfortunately, this was mere wishful thinking on his part, for seventeen years later another Cub (albeit a former one) made newspaper headlines after a deranged young woman nearly killed him.

According to the New York Times, 19-year-old Ruth Ann Steinhagen, a 6-foot dark-haired typist, had a “twisted fascination” for Philadelphia Phillies player Eddie Waitkus that began in 1947 when he played for the Cubs. The “bobby sox baseball fan” had collected hundreds of clippings about him and had built a shrine to him in her room. When he was traded to the Phillies in December 1948, she wanted to move to Philadelphia to be near him. Her mother said that Ruth was “so crazy” about Waitkus, a man whom she had never met, that she tried to learn to speak Lithuanian when she found out he was of Lithuanian ancestry. (Left, Chicago Cubs first baseman Eddie Waitkus in 1941, his rookie year. Click on image to enlarge.)

According to the New York Times, 19-year-old Ruth Ann Steinhagen, a 6-foot dark-haired typist, had a “twisted fascination” for Philadelphia Phillies player Eddie Waitkus that began in 1947 when he played for the Cubs. The “bobby sox baseball fan” had collected hundreds of clippings about him and had built a shrine to him in her room. When he was traded to the Phillies in December 1948, she wanted to move to Philadelphia to be near him. Her mother said that Ruth was “so crazy” about Waitkus, a man whom she had never met, that she tried to learn to speak Lithuanian when she found out he was of Lithuanian ancestry. (Left, Chicago Cubs first baseman Eddie Waitkus in 1941, his rookie year. Click on image to enlarge.)

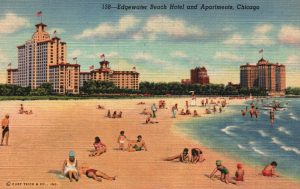

In mid-June 1949, the 29-year-old Waitkus was in Chicago with the Phillies to play a series against his old team. The Phillies stayed at the Edgewater Beach Hotel, and on June 13 Steinhagen checked into the same hotel with a suitcase, a .22 caliber rifle, and a paring knife.

On June 14, she sent Waitkus a note asking him to come to her room as she had “something of importance” to tell him. When he knocked on her door, she put the paring knife in her skirt pocket, intending to stab him as soon as he came in. But he quickly walked past her, sat in a chair, and asked her what she wanted. (The Edgewater Beach Hotel in 1949.)

On June 14, she sent Waitkus a note asking him to come to her room as she had “something of importance” to tell him. When he knocked on her door, she put the paring knife in her skirt pocket, intending to stab him as soon as he came in. But he quickly walked past her, sat in a chair, and asked her what she wanted. (The Edgewater Beach Hotel in 1949.)

She said, “I have a surprise for you” and reached into the closet and pulled out the rifle. “For two years you’ve bothered me,” she told him. “Now you’re going to die.” After shooting him in the right breast, she told the police that she started to reload the gun to shoot herself, but “blacked out” for a bit. She then phoned hotel authorities, telling them that “I just shot a man.”

She said, “I have a surprise for you” and reached into the closet and pulled out the rifle. “For two years you’ve bothered me,” she told him. “Now you’re going to die.” After shooting him in the right breast, she told the police that she started to reload the gun to shoot herself, but “blacked out” for a bit. She then phoned hotel authorities, telling them that “I just shot a man.”

This photograph appeared in the Chicago Tribune on June 15, 1949. (Click on image to enlarge.) Caption: “Room 1297A at the Edgewater Beach Hotel where baseball player Eddie Waitkus was shot. At right is the chair where Waitkus sat when Ruth Steinhagen fired her rifle. At left is a dresser with a martini glass and drink mixes.” The Edgewater Beach Hotel closed in 1967, and its main buildings were soon demolished.

This photograph appeared in the Chicago Tribune on June 15, 1949. (Click on image to enlarge.) Caption: “Room 1297A at the Edgewater Beach Hotel where baseball player Eddie Waitkus was shot. At right is the chair where Waitkus sat when Ruth Steinhagen fired her rifle. At left is a dresser with a martini glass and drink mixes.” The Edgewater Beach Hotel closed in 1967, and its main buildings were soon demolished.

Waitkus was taken to Illinois Masonic Hospital in critical condition with a collapsed right lung. Police booked Steinhagen on a charge of assault with intent to murder.

When interviewed by State’s Attorney John S. Boyle she said: “I’m not really sorry. I’m sorry Eddie has to suffer so. I’m sorry it had to be him. But I had to shoot somebody. Only in that way could I relieve the nervous tension I’ve been under the last two years. The shooting has relieved that tension.” Right: In this photograph from the Chicago Tribune, Ruth Steinhagen sits in a police wagon after her arrest for shooting Eddie Waitkus. (Click on image to enlarge.)

When interviewed by State’s Attorney John S. Boyle she said: “I’m not really sorry. I’m sorry Eddie has to suffer so. I’m sorry it had to be him. But I had to shoot somebody. Only in that way could I relieve the nervous tension I’ve been under the last two years. The shooting has relieved that tension.” Right: In this photograph from the Chicago Tribune, Ruth Steinhagen sits in a police wagon after her arrest for shooting Eddie Waitkus. (Click on image to enlarge.)

Police learned that Steinhagen’s mother, Edith, had urged her daughter to get professional help. Ruth did meet with two psychiatrists, but they could not help her with her obsession with Waitkus. Her father, Walter, and sister, Rita, had tried reasoning with her, but they, too, got nowhere. (Left: The caption of this wire photo notes that Ruth “is shown peering from her jail cell in Chicago after her arrest.” Click on image to enlarge.)

Police learned that Steinhagen’s mother, Edith, had urged her daughter to get professional help. Ruth did meet with two psychiatrists, but they could not help her with her obsession with Waitkus. Her father, Walter, and sister, Rita, had tried reasoning with her, but they, too, got nowhere. (Left: The caption of this wire photo notes that Ruth “is shown peering from her jail cell in Chicago after her arrest.” Click on image to enlarge.)

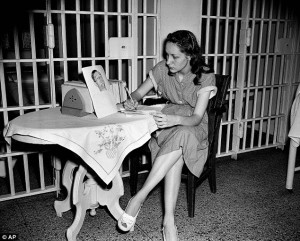

Ruth Steinhagen works on her autobiography at the request of Dr. William H. Haines, her court-appointed psychiatrist. At the opening of her twelve-page life story, she wrote: “In my entire life, I don’t think there has ever been one thing that turned out the way I wanted it to.” In this posed photograph, she sits in her jail cell at an attractive table with a picture of Eddie Waitkus propped before her. (Click on image to enlarge.)

Ruth Steinhagen works on her autobiography at the request of Dr. William H. Haines, her court-appointed psychiatrist. At the opening of her twelve-page life story, she wrote: “In my entire life, I don’t think there has ever been one thing that turned out the way I wanted it to.” In this posed photograph, she sits in her jail cell at an attractive table with a picture of Eddie Waitkus propped before her. (Click on image to enlarge.)

Ruth Steinhagen not only wrote but also read. Here she is poring over her Bible while in her cell in the Cook County jail.

Ruth Steinhagen not only wrote but also read. Here she is poring over her Bible while in her cell in the Cook County jail.

She had begun making plans to shoot the ballplayer in early May, buying the rifle in a Chicago pawn shop. Rita told police that she had heard her sister threaten to “get Eddie,” but she never took Ruth seriously. “We thought she was just talking,” Rita said.

By June 16 (the day before the above photo of Ruth reading her Bible was taken), Waitkus’s condition was upgraded from “critical” to “good.” The hospital report added that he had “taken a turn for the better, but was not quite out of danger.” A few days later, however, after Waitkus underwent a minor operation to draw blood from his punctured lung, the hospital said that he was “breathing easier” and showed “marked improvement.”

Right: Ex-Cub Eddie Waitkus smiles weakly from his hospital bed in the Illinois Masonic Hospital in Chicago. His father, Stephen Waitkus, holds up his arm for an attempted wave while a nurse stands nearby. This wire photo is dated June 18, 1949, just four days after the young man was shot by, according to the New York Times, “19-year-old typist” Ruth Ann Steinhagen, “a girl fan whom he did not know.” (Click on image to enlarge.)

Right: Ex-Cub Eddie Waitkus smiles weakly from his hospital bed in the Illinois Masonic Hospital in Chicago. His father, Stephen Waitkus, holds up his arm for an attempted wave while a nurse stands nearby. This wire photo is dated June 18, 1949, just four days after the young man was shot by, according to the New York Times, “19-year-old typist” Ruth Ann Steinhagen, “a girl fan whom he did not know.” (Click on image to enlarge.)

Left: This photograph appeared in newspapers on June 21, 1949 (click on image to enlarge). One caption reads: “Ruth Steinhagen (right) tries her hand at first base, Eddie Waitkus’ position, in practice baseball session among inmates at the jail. Mrs. Ann Markov, chief matron, takes the ump’s role.” Note Steinhagen’s high heels. Other obviously posed photographs show Steinhagen in jail admiring photos of Waitkus.

Left: This photograph appeared in newspapers on June 21, 1949 (click on image to enlarge). One caption reads: “Ruth Steinhagen (right) tries her hand at first base, Eddie Waitkus’ position, in practice baseball session among inmates at the jail. Mrs. Ann Markov, chief matron, takes the ump’s role.” Note Steinhagen’s high heels. Other obviously posed photographs show Steinhagen in jail admiring photos of Waitkus.

Right: Although Eddie Waitkus’s condition had improved by the end of June, he was not yet ready to go home. He did, however, have one important task to do on June 30 that would get him out of his sick bed for a few hours. The caption of this wire photo reads: “Baseball star Eddie Waitkus is shown with nurse Alice Klopfer today as he left the Illinois Masonic Hospital to appear in Chicago’s Felony Court to testify at the arraignment of Ruth Steinhagen, 19, who was charged with assault with intent to murder.” Waitkus was scheduled to return to the hospital “for further observation” after his testimony. (Click on image to enlarge.)

Right: Although Eddie Waitkus’s condition had improved by the end of June, he was not yet ready to go home. He did, however, have one important task to do on June 30 that would get him out of his sick bed for a few hours. The caption of this wire photo reads: “Baseball star Eddie Waitkus is shown with nurse Alice Klopfer today as he left the Illinois Masonic Hospital to appear in Chicago’s Felony Court to testify at the arraignment of Ruth Steinhagen, 19, who was charged with assault with intent to murder.” Waitkus was scheduled to return to the hospital “for further observation” after his testimony. (Click on image to enlarge.)

On June 30, both Eddie Waitkus and Ruth Steinhagen appeared in the Felony Courtroom of Judge Matthew D. Hartigan of Chicago. From the Chicago Daily Tribune: “Dr. William H. Haines, head of the Criminal court behavior clinic, was the only witness at the sanity hearing. He testified Miss Steinhagen is a victim of schizophrenia (split personality) and that in his opinion she would be unable to co-operate with counsel, altho[ugh] he believed she understood the nature of the charge against her.” (A year later, Haines published a “Case History of Ruth Steinhagen” in the American Journal of Psychiatry.)

This June 16, 1949, wire photograph is titled “Ruth Confers with Parents.” The caption reads: “Chicago: Ruth Steinhagen confers with her parents, Walter (left) and Edith (right) before arraignment today (6/16) in felony court on charge of attempted murder. She shot Phillies’ baseball star Eddie Waitkus once in the chest. Deputy bailiff Jennie Du Bray is in background.” (Click to enlarge.)

This June 16, 1949, wire photograph is titled “Ruth Confers with Parents.” The caption reads: “Chicago: Ruth Steinhagen confers with her parents, Walter (left) and Edith (right) before arraignment today (6/16) in felony court on charge of attempted murder. She shot Phillies’ baseball star Eddie Waitkus once in the chest. Deputy bailiff Jennie Du Bray is in background.” (Click to enlarge.)

A crowded Chicago courtroom on June 30, 1949, includes, from left to right: defense attorney Michael Brodkin, Ruth Steinhagen addressing the court, policewoman Mary Henneberry, defense attorney George Bieber (looking up), Eddie Waitkus in a wheelchair, and nurse Alice Klopfer behind him. The unseen man holding the papers at far right is State’s Attorney John S. Boyle. (Click on image to enlarge.)

Part of the caption on this wire photograph reads: “Ruth Steinhagen, flanked by attorney Michael Brodkin and policewoman, cranes neck to see her hero Eddie Waitkus in wheelchair at Felony court here today (6/30).” What with Ruth just a few feet from the stoic Eddie, I can’t help but think that a circus-like atmosphere pervaded the jammed courtroom. (Click on image to enlarge.)

Part of the caption on this wire photograph reads: “Ruth Steinhagen, flanked by attorney Michael Brodkin and policewoman, cranes neck to see her hero Eddie Waitkus in wheelchair at Felony court here today (6/30).” What with Ruth just a few feet from the stoic Eddie, I can’t help but think that a circus-like atmosphere pervaded the jammed courtroom. (Click on image to enlarge.)

Waitkus, in a wheelchair, testified that Steinhagen shot him after he entered her hotel room. A jury of six men and six women found her insane, and Chief Justice James J. McDermott of the Criminal Court ordered her committed to the Kankakee State Hospital for treatment (located some fifty miles south of Chicago).

Eddie Waitkus spent a month in the hospital. Like Billy Jurges, he recovered from his injuries and resumed his baseball career, winning the sport’s “Comeback of the Year” award in 1950. Right: As he stands surrounded by gifts, Eddie Waitkus acknowledges the applause of fans during “Eddie Waitkus Night,” August 19, 1949, at the Phillies’ Shibe Park. He is in uniform for the first time since he was shot. (Click on image to enlarge.)

Eddie Waitkus spent a month in the hospital. Like Billy Jurges, he recovered from his injuries and resumed his baseball career, winning the sport’s “Comeback of the Year” award in 1950. Right: As he stands surrounded by gifts, Eddie Waitkus acknowledges the applause of fans during “Eddie Waitkus Night,” August 19, 1949, at the Phillies’ Shibe Park. He is in uniform for the first time since he was shot. (Click on image to enlarge.)

In March 1954, Philadelphia sold Eddie Waitkus to the Baltimore Orioles for $40,000. In July 1955 he rejoined the Phillies, retiring in October that year. Late in life he taught the fine points of hitting to youths at the Ted Williams baseball camp in Lakeville, Massachusetts. (Among Waitkus’s best pupils one summer was the grandson of Billy Jurges.)

Ruth Steinhagen spent several years at the Kankakee State Hospital undergoing therapy for her mental illnesses. She was released from the hospital on April 17, 1952, having been certified sane by hospital officials. Left: Ruth Steinhagen (second from left), age 22, walks between her parents, Edith and Walter Steinhagen, and with attorney Michael Brodkin the day following her release from the hospital. (Click to enlarge.)

Ruth Steinhagen spent several years at the Kankakee State Hospital undergoing therapy for her mental illnesses. She was released from the hospital on April 17, 1952, having been certified sane by hospital officials. Left: Ruth Steinhagen (second from left), age 22, walks between her parents, Edith and Walter Steinhagen, and with attorney Michael Brodkin the day following her release from the hospital. (Click to enlarge.)

Right: Ruth Steinhagen talks with Deputy Chief Bailiff George C. Ibsen at the Cook County sheriff’s office after her 1952 hospital release. That year Bernard Malamud published his first novel, The Natural, which included a paragraph in which a woman shoots ballplayer Roy Hobbs. It’s possible that the wounding of Waitkus (and maybe that of Billy Jurges) inspired Malamud. See this excellent article by Rob Edelman. (Click image to enlarge.)

Right: Ruth Steinhagen talks with Deputy Chief Bailiff George C. Ibsen at the Cook County sheriff’s office after her 1952 hospital release. That year Bernard Malamud published his first novel, The Natural, which included a paragraph in which a woman shoots ballplayer Roy Hobbs. It’s possible that the wounding of Waitkus (and maybe that of Billy Jurges) inspired Malamud. See this excellent article by Rob Edelman. (Click image to enlarge.)

In a 1988 New York Times interview with Edward Waitkus, Jr., he observed that “the shooting changed my father a great deal, as you might imagine. Before, he was a very outgoing person. Then he became almost paranoid about meeting new people . . . . When [Steinhagen] was about to be released from the mental hospital after only a few years–they said she had fully recovered–my father and my family fought to keep her in. My father feared for his life.”

Eddie Waitkus died of cancer on September 16, 1972, at age 53. As for Ruth Steinhagen, in 1970 she, her sister, and her parents bought a house on Chicago’s Northwest Side, where for decades she lived in seclusion. Her father died in 1990 and her mother died two years later. “Ruth keeps to herself, but she is always very pleasant,” her next-door neighbor told John Theodore, author of Baseball’s Natural: The Story of Eddie Waitkus (2002). “She’s a loner-type, mostly stays in her house with her sister,” a young woman remarked. “We really don’t see them much or know anything about them,” said a man who lives across the street.

In 2007, Ruth’s sister, Rita Pendl, died at age 76, and on December 29, 2012, 83-year-old Ruth died of a subdural hematoma caused by an accidental fall in her home (center). According to her obituary in the March 14, 2013, Chicago Tribune, “Her death had gone unreported and was only discovered when the Tribune was searching death records for another story.”

In 2007, Ruth’s sister, Rita Pendl, died at age 76, and on December 29, 2012, 83-year-old Ruth died of a subdural hematoma caused by an accidental fall in her home (center). According to her obituary in the March 14, 2013, Chicago Tribune, “Her death had gone unreported and was only discovered when the Tribune was searching death records for another story.”

Above right: Ruth Steinhagen lived in the center house, situated in the 5000 block of Sawyer Avenue on Chicago’s Northwest Side. Photograph taken by Terrence Antonio James of the Chicago Tribune on March 11, 2013. (Click on image to enlarge.)

Left: The caption of this June 15, 1949, wire photo reads: “Mrs. Edith Steinhagen (left) and her daughter, Rita, 18, mother and sister of Ruth Steinhagen, who shot baseball star Eddie Waitkus here [in Chicago] last night, are shown at their home as they hear the news.” Mr. and Mrs. Steinhagen and their two daughters moved to another Chicago house in 1970.

Left: The caption of this June 15, 1949, wire photo reads: “Mrs. Edith Steinhagen (left) and her daughter, Rita, 18, mother and sister of Ruth Steinhagen, who shot baseball star Eddie Waitkus here [in Chicago] last night, are shown at their home as they hear the news.” Mr. and Mrs. Steinhagen and their two daughters moved to another Chicago house in 1970.

Author John Theodore spent years trying to talk to Ruth Steinhagen for his biography of Eddie Waitkus, but was not successful. From the Tribune‘s obituary of her:

“It was very frustrating not being able to interview her,” [Theodore] said. “I made many phone calls, knocked on her door several times . . . talked to neighbors. I got nowhere. She would never answer her door. And the phone conversations were very short: ‘Oh, that’s in the past, so long ago. I don’t want to talk about it,’ she’d say.

“She seemed upset when I talked to her, nearly hysterical. But to be honest with you, I really didn’t know if I was talking to Ruth or sister Rita. I didn’t want to invade her privacy any more than I had. So I decided to stop–or risk becoming a stalker myself.”

Incidentally, while working on this web page I, too, tried contacting Ruth Steinhagen. Not surprisingly, she never answered my letters.

Pingback: Wrigley Ivy: Jack Bales on the Chicago Cubs | bavatuesdays

Very interesting about the life of Violet Valli. Nice of her nephew to contact you.

It was extremely interesting talking to him… and I spent quite a bit of time researching both shootings. Thanks for writing.

Very interesting piece of research.

Do you know what happened to Jurges’ love letters to Violet – the ones involved in a later “blackmail” plot involving Lucius Barnett?

Did you come across anything relating to Violet’s former career in the Vanities chorus line or her work in confessions magazines in New York?

Thanks for writing. I am well aware of the attempted blackmail plot and Violet’s modeling work with confessions magazines, but all I know is what the papers wrote. I’ve added a bit about these topics to my website, and I appreciate your asking about them.

It is my understanding that Violet’s six month show after the shootings was cut short after the curiosity wore off and due to her lack of talent. Throughout her life she talked about her show girl past. In fact, when I wrapped up her affairs at her nursing home after her death, the day care provider commented on how she also talked about her show girl past.

Peter, I did not know that, and I sure appreciate your comment. It’s absolutely fascinating. I wish I knew more about that period of her life. Thank you!

My wife’s Uncle played with Waitkus on the Cubs. Heard interesting stories about the team back then. Shame about Waitkus career afterwards. Someone who earned 4 bronze stars during WWII in the Pacific Theatre. Wish his career had turned out differently.

Thanks for emailing, Tony. I read quite a few articles that mentioned that the shooting took both a physical and emotional toll on Eddie. By the way, I am revising the section on Violet Popovich and hope to have it up by the end of the year. (I’m doing quite a bit more research on her.)

I am the grand-daughter of Billy Jurges. You mention in the paragraph below that Billy Jurges had a son. This is not true. One daughter, my mother. No other children.

March 1954, Philadelphia sold Eddie Waitkus to the Baltimore Orioles for $40,000. In July 1955 he rejoined the Phillies, retiring in October that year. Late in life he taught the fine points of hitting to youths at the Ted Williams baseball camp in Lakeville, Massachusetts. (Among Waitkus’s best pupils one summer was the son of Billy Jurges.)

You are exactly right, and thanks very much. I meant to say grandson, and I immediately made the correction. I appreciate your letting me know.

Thanks for this article. My grandfather, Carl A. Carlson was a builder and developer in Chicago and Evanston. He built the Hotel Carlos and another called the Fernwood. Both hotels were favorite residences for the Cubs players of the day.

This is just fascinating and I did not know it at all. Thanks so much for telling me!

My twin brother and I were introduced to Eddie Waitkus in 1950 at the Palm Pavilion on Clearwater Beach by Charlie Pride, our uncle who was a popular car salesman. We were 15, and Waitkus was Don’s hero since he played first base on Clearwater High School’s team. (I was an aspiring shortstop and admired Granny Hamner.) That was in the off-season, and Waitkus, tanned and trimmed, often ran wind sprints to get ready for his return to the Phillies.